Emissions testing is a core part of roadworthiness tests in many countries today and is more than likely to become more rigorous in the future. In this article, the Autodata team examines the history of emissions testing and how it’s likely to develop.

Workshop emissions testing typically focuses on carbon monoxide emissions, but also includes other pollutant content such as nitrogen oxide (NOx), hydrocarbons, and heavy particles. Increasingly, countries and trading blocs are also instituting laboratory checks on new vehicle models – which is frequently driven by the desire to limit carbon dioxide (CO2) output. Approximately 25 percent of global CO2 emissions are related to transport, of which passenger cars and vans constitute 13 percent.

The first emissions tests were focused on air quality and sought to reduce overall particle emissions. The first legislation on emissions testing was passed in California for vehicles sold in model year 1966 onwards, with the U.S. as a whole following in 1968. The first EU standards for passenger cars were introduced in 1970 and remained the same until 1992, when the new harmonised Euro 1 standards mandated the switch to unleaded petrol and the universal fitting of catalytic convertors.

Standards for emissions tests have continued to become more stringent. The latest EU standard, Euro 6, establishes a maximum level of 80mg of NOx per km for new diesel vehicles and just 60mg for petrol – compared to 1g/km in the Euro 1 standards set for petrol and diesel NOx in 1992. That’s 6-8 percent of the original requirement.

Manufacturers have adopted a variety of measures to improve the performance of their models on these tests. Some of these have fallen foul of regulators. For example, the so-called ‘defeat devices’ used to bypass or disable emission controls for performance driving, or, conversely, tamp down emissions while the engine is running without acceleration or wheel rotation. Such devices – which can include software in the Engine Control Module (ECM) – mean the vehicle passes emissions testing in the workshop but would not be compliant on the road.

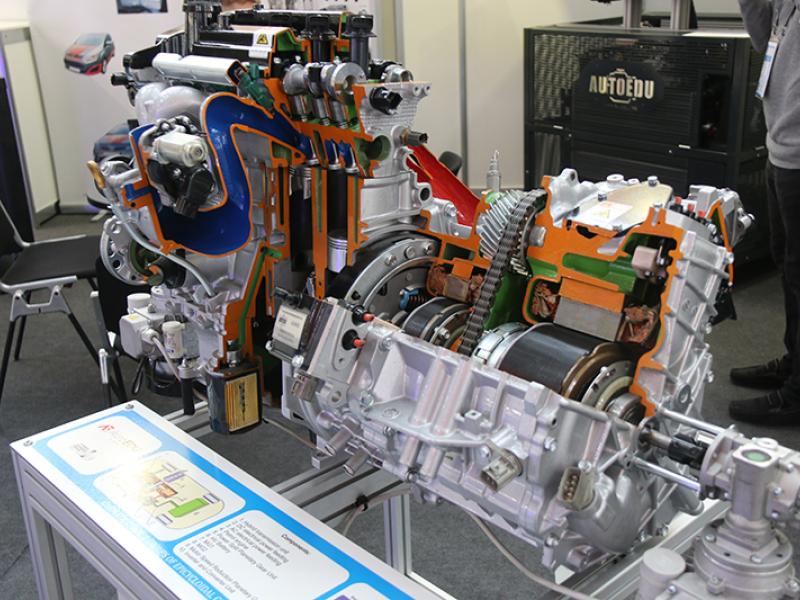

While high-profile investigations have captured headlines, there is also a growing gap between laboratory tests and real-world performance. The International Council on Clean Transportation reported in 2015 as much as a 38 percent gap between official vehicle CO2 emissions and on-the-road performance. Stop-start fuel saving systems and hybrid powertrains are also proving more effective at reducing emissions in the laboratory than on the road.

To help resolve the discrepancies between laboratory or workshop results and real-world conditions, more countries are opting to include requirements for real-world driving tests as well as powertrain checks for each configuration. In the U.K., the Ministry of Transport (MoT) head of test policy at the Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA) has signalled the need for tougher in-workshop emissions tests; and, that these would be partly informed by national emissions targets.

The MoT test changes in 2018 introduced stricter diesel emissions tests as well as a check for diesel particulate filter (DPF) tampering. This resulted in a 63 percent increase in emissions-related failures from May 2018 to February 2019 when compared to the previous 12 months. These changes particularly impacted light commercial vehicles (LCVs), which showed a 116 percent increase in emissions-related failures during the same period.

DPFs are designed to trap soot particles and became standard for diesel cars in 2009 to comply with Euro 5. A car equipped with a DPF will fail the MoT test if blue or oily smoke is emitted from the exhaust or if there are visible signs of tampering. Previously a common – if inadvisable – consumer fix for a blocked DPF was to cut a hole in the DPF exterior and remove the internals before welding the hole shut. Since the former test only required a visual inspection rather than emissions analysis, it was possible to pass the MoT test despite the DPF being non-functional.

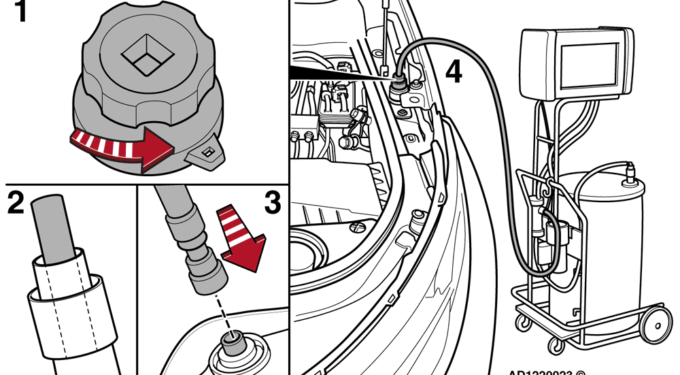

To assist workshops in meeting new road test requirements around emissions, Autodata has introduced a diesel exhaust gas aftertreatment module. This module includes information on the usage of diesel aftergas products, adblue topups, DPF regeneration, and how to reset selective catalyst reduction (SCR) units. Autodata has seen significant usage of the module, with over 98,000 requests for data in the past year.

“Emissions testing is a great example of the industry need for accurate, up-to-date vehicle data,” Chris Wright, Managing Director of Autodata, said. “With changes to both the regulatory climate and how older vehicles are classified, it’s vital to have access to the recommended idle speeds, oil temperatures for testing, lambda readings at idle, and more. We’re pleased to be able to support the aftermarket with a wide range of technical data and we will continue to do so as standards evolve.”

Autodata’s online workshop application is used by over 85,000 workshops in 132 countries and features tuning and emissions data for 99 percent of the vehicles users selected in the past 30 days. For more information on Autodata or to try it yourself, visit www.autodata-group.com.

The past, present, and future of emissions testing

The past, present, and future of emissions testing

Workshop Equipment

Saturday, 05 March 2022